W

WOttoman culture evolved over several centuries as the ruling administration of the Turks absorbed, adapted and modified the various native cultures of conquered lands and their peoples. There was a strong influence from the customs and languages of Islamic societies, notably Arabic, while Persian culture had a significant contribution through the heavily Persianized Seljuq Turks, the Ottomans' predecessors. Despite newer added amalgamations, the Ottoman dynasty, like their predecessors in the Sultanate of Rum and the Seljuk Empire, were thoroughly Persianised in their culture, language, habits and customs, and therefore, the empire has been described as a Persianate empire." Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire had substantial subject populations of Orthodox subjects, Armenians, Jews and Assyrians, who were allowed a certain amount of autonomy under the confessional millet system of Ottoman government, and whose distinctive cultures enriched that of the Ottoman state.

W

WThe Armeno-Turkish alphabet is a version of the Armenian alphabet sometimes used to write Ottoman Turkish until 1928, when the Latin-based modern Turkish alphabet was introduced. The Armenian script was not just used by ethnic Armenians to write the Turkish language, but also by the non-Armenian Ottoman Turkish elite.

W

WWojciech Bobowski or Ali Ufki was a Polish, later Turkish musician and dragoman in the Ottoman Empire. He translated the Bible into Ottoman Turkish, composed an Ottoman Psalter, based on the Genevan metrical psalter, and wrote a grammar of the Ottoman Turkish language. His musical works are considered among the most important in 17th-century Ottoman music.

W

WCariye or Cariyes was a title and term used for category of enslaved women concubines in the Islamic world of the Middle East. They are particularly known in history from the era of the Ottoman Empire, where they legally existed until the mid-19th century.

W

WUnder the Ottoman Empire's millet system, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmi under Ottoman law in exchange for loyalty to the state and payment of the jizya tax.

W

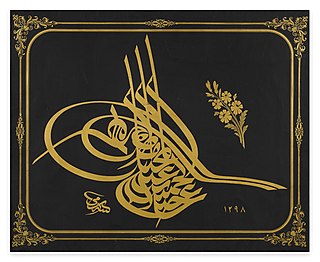

WEvery sultan of the Ottoman Empire had his own monogram, called the tughra, which served as a royal symbol. A coat of arms in the European heraldic sense was created in the late 19th century. Hampton Court requested from the Ottoman Empire a coat of arms to be included in their collection. As the coat of arms had not been previously used in the Ottoman Empire, it was designed after this request, and the final design was adopted by Sultan Abdul Hamid II on 17 April 1882.

W

WThe Constantinople observatory of Taqi ad-Din, founded in Constantinople by Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf in 1577, was one of the largest astronomical observatories in medieval world. However, it only existed for a few years and was destroyed in 1580.

W

WDevshirme was the Ottoman practice of forcibly recruiting soldiers and bureaucrats from among the children of their Balkan Christian subjects. It is first mentioned in written records in 1438, but probably started earlier. It created a faction of soldiers and officials loyal to the Sultan. It counterbalanced the Turkish nobility, who sometimes opposed the Sultan. The system produced all of the grand viziers, from the 1400s to the 1600s. This was the second most powerful position in the Ottoman empire, after the sultan. The devshirme also produced most of the Ottoman empire's provincial governors, military commanders, and divans during that period.

W

WDiwani is a calligraphic variety of Arabic script, a cursive style developed during the reign of the early Ottoman Turks. It reached its height of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566).

W

WGhilman were slave-soldiers and/or mercenaries in the armies throughout the Islamic world, such as the Abbasid, Samanid, Ottoman, Safavid, Afsharid and Qajar empires. Islamic states from the early 9th century to the early 19th century consistently deployed slaves as soldiers, a phenomenon that was very rare outside of the Islamic world.

W

WHarem properly refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. This private space has been traditionally understood as serving the purposes of maintaining the modesty, privilege, and seclusion of women from other men. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic servants, and other unmarried female relatives. In harems of the past, concubines, which were enslaved women, were also housed in the harem. In former times some harems were guarded by eunuchs who were allowed inside. The structure of the harem and the extent of monogamy or polygamy has varied depending on the family's personalities, socio-economic status, and local customs. Similar institutions have been common in other Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilizations, especially among royal and upper-class families, and the term is sometimes used in other contexts. In traditional Persian residential architecture the women's quarters were known as andaruni (Persian: اندرونی; meaning inside, and in the Indian subcontinent as zenana.

W

WEsmâ Ibret Hanim was an Ottoman calligrapher and poet, noted as the most successful female calligrapher of her day.

W

WThe Ottoman Empire used anthems since its foundation in the late 13th century, but did not use a specific imperial or national anthem until the 19th century. During the reign of Mahmud II, when the military and imperial band were re-organized along Western lines, Giuseppe Donizetti was invited to head the process. Donizetti Pasha, as he was known in the Ottoman Empire, composed the first Western-style imperial anthem, the Mahmudiye Marşı.

W

WIslamic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy, in the languages which use Arabic alphabet or the alphabets derived from it. It includes Arabic, Persian, Ottoman, and Indian calligraphy. It is known in Arabic as khatt Arabi, which translates into Arabic line, design, or construction.

W

Wİsmail Zühdi Efendi was an Ottoman calligrapher. “Efendi” is a title of nobility, so this name can also be rendered İsmail Zühdi.

W

WThe Kapi Agha, formally called the Agha of the Gate of Felicity, was the head of the eunuch servants of the Ottoman Seraglio until the late 16th century, when this post was taken over by the Kizlar Agha. In juxtaposition with the latter office, also known as the Chief Black Eunuch as its holders were drawn from Black African slaves, the Kapi Agha is also known as the Chief White Eunuch.

W

WKaramanlı Turkish is both a form of written Turkish and a dialect of Turkish spoken by the Karamanlides, a community of Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians in Ottoman Turkey. The official Ottoman Turkish was written in the Arabic script, but the Karamanlides used the Greek alphabet to write their form of Turkish. Karamanlı Turkish had its own literary tradition and produced numerous published works in print during the 19th century, some of them published by Evangelinos Misailidis by the Anatoli or Misailidis publishing house.

W

WThe kizlar agha, formally the agha of the House of Felicity, was the head of the eunuchs who guarded the imperial harem of the Ottoman sultans in Constantinople.

W

WKuruş, also qirsh, ersh, gersh, grush and grosi, are all names for currency denominations in and around the territories formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. The variation in the name stems from the different languages it is used in and the different transcriptions into the Latin alphabet. In European languages, the kuruş was known as the piastre.

W

WThe language of the court and government of the Ottoman Empire was Ottoman Turkish, but many other languages were in contemporary use in parts of the empire. Although the minorities of the Ottoman Empire were free to use their language amongst themselves, if they needed to communicate with the government they had to use Ottoman Turkish.

W

WMahmud Celaleddin Efendi was an Ottoman calligrapher.

W

WMehmed Shevki Efendi, was a prominent Ottoman calligrapher. He is known for his Thuluth-Naskh works, and his style developed into the Shevki Mektebi school, which many contemporary calligraphers in the style take as a reference.

W

WMüneccimbaşı was the title given to the chief court astrologer in the Ottoman Empire. The title was held in succession from the 15th century until the demise of the Empire.

W

WMustafa Râkim (1757–1826), was an Ottoman calligrapher. He extended and reformed Hâfiz Osman's style, placing greater emphasis on technical perfection, which broadened the calligraphic art to encompass the Sülüs script as well as the Nesih script.

W

WGracia Mendes Nasi was a Portuguese intellectual and one of the wealthiest Jewish women of Renaissance Europe. She married Francisco Mendes/Benveniste. She was the aunt and business partner of Joao Micas, who became a prominent figure in the politics of the Ottoman Empire. She also developed an escape network that saved hundreds of Conversos from the Inquisition. Her name Gracia is Spanish for the Hebrew Hannah, which means Grace; she was also known by her Christianized name Beatrice de Luna.

W

WJoseph Nasi, known in Portuguese as João Micas, was a Portuguese Sephardi diplomat and administrator, member of the House of Mendes/Benveniste, nephew of Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi, and an influential figure in the Ottoman Empire during the rules of both Sultan Suleiman I and his son Selim II. He was a great benefactor of the Jewish people.

W

WTurkish or Ottoman illumination covers non-figurative painted or drawn decorative art in books or on sheets in muraqqa or albums, as opposed to the figurative images of the Ottoman miniature. In Turkish it is called “tezhip”, meaning “ornamenting with gold”. It was a part of the Ottoman Book Arts together with the Ottoman miniature (taswir), calligraphy (hat), Islamic calligraphy, bookbinding (cilt) and paper marbling (ebru). In the Ottoman Empire, illuminated and illustrated manuscripts were commissioned by the Sultan or the administrators of the court. In Topkapi Palace, these manuscripts were created by the artists working in Nakkashane, the atelier of the miniature and illumination artists. Both religious and non-religious books could be illuminated. Also sheets for albums levha consisted of illuminated calligraphy (hat) of tughra, religious texts, verses from poems or proverbs, and purely decorative drawings.

W

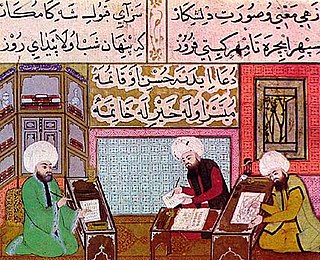

WOttoman miniature or Turkish miniature was a Turkish art form in the Ottoman Empire, which can be linked to the Persian miniature tradition, as well as strong Chinese artistic influences. It was a part of the Ottoman book arts, together with illumination (tezhip), calligraphy (hat), marbling paper (ebru), and bookbinding (cilt). The words taswir or nakish were used to define the art of miniature painting in Ottoman Turkish. The studios the artists worked in were called Nakkashanes.

W

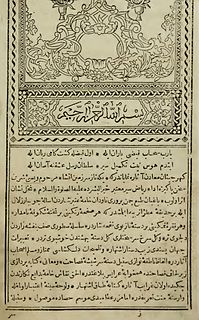

WThe Ottoman Turkish alphabet is a version of the Arabic alphabet used to write Ottoman Turkish until 1928, when it was replaced by the Latin-based modern Turkish alphabet.

W

WA Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the Persian language, culture, literature, art and/or identity.

W

WPhanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar, the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is located, who traditionally occupied four important positions in the Ottoman Empire: Voivode of Moldavia, Voivode of Wallachia, Grand Dragoman, and Grand Dragoman of the Fleet. Despite their cosmopolitanism and often-Western education, the Phanariots were aware of their Hellenism; according to Nicholas Mavrocordatos' Philotheou Parerga, "We are a race completely Hellenic".

W

WSami Efendi (1858-1912), was an Ottoman calligrapher.

W

WThe selamlik or sélamlique was the portion of an Ottoman palace or house reserved for men; as contrasted with the seraglio, which is reserved for women and forbidden to men.

W

WA seraglio or serail is the sequestered living quarters used by wives and concubines in an Ottoman household. The term harem is a generic term for domestic spaces reserved for women in a Muslim family, which can also refer to the women themselves. The Ottoman Imperial Harem was known in Ottoman Turkish as Harem-i Hümâyûn.

W

WThe Surname-i Hümayun, were albums that commemorated celebrations in the Ottoman Empire in pictorial and textual detail. Such celebrations included mainly imperial weddings and circumcision festivals. These albums were commissioned by the Ottoman Imperial family, usually by the Sultan presiding at the time. The Surname recounts the festivities in order of when the events took place, which includes in detail processions, grand entrance of the Sultan, feasts, entertainers, musicians, dancers, gift giving, firework displays, circumcision and wedding ceremonies. Although many of the Surnames were made to celebrate circumcisions of Ottoman Princes, the first Surname was commissioned in 1524 for a wedding ceremony.

W

WA tughra is a calligraphic monogram, seal or signature of a sultan that was affixed to all official documents and correspondence. It was also carved on his seal and stamped on the coins minted during his reign. Very elaborate decorated versions were created for important documents that were also works of art in the tradition of Ottoman illumination, such as the example of Suleiman the Magnificent in the gallery below.

W

WThe composite Turco-Persian tradition or Turco-Iranian tradition, refers to a distinctive culture that arose in the 9th and 10th centuries in Khorasan and Transoxiana. It was Persianate in that it was centered on a lettered tradition of Iranian origin and it was Turkic insofar as it was founded by and for many generations patronized by rulers of Turkic heredity. In subsequent centuries, the Turco-Persian culture would be carried on further by the conquering peoples to neighbouring regions, eventually becoming the predominant culture of the ruling and elite classes of South Asia, Central Asia and Tarim basin and large parts of West Asia.

W

WTurquerie was the Orientalist fashion in Western Europe from the 16th to 18th centuries for imitating aspects of Turkish art and culture. Many different Western European countries were fascinated by the exotic and relatively unknown culture of Turkey, which was the center of the Ottoman Empire, and at the beginning of the period the only power to pose a serious military threat to Europe. The West had a growing interest in Turkish-made products and art, including music, visual arts, architecture, and sculptures. This fashionable phenomenon became more popular through trading routes and increased diplomatic relationships between the Ottomans and the European nations, exemplified by the Franco-Ottoman alliance in 1715. Ambassadors and traders often returned home with tales of exotic places and souvenirs of their adventures.

W

WJean Baptiste Vanmour or Van Mour was a Flemish-French painter, remembered for his detailed portrayal of life in the Ottoman Empire during the Tulip Era and the rule of Sultan Ahmed III.

W

WWomen in the Ottoman Empire had different rights and positions depending on their religion and class. Ottoman women were permitted to participate in the legal system, purchase and sell property, inherit and bequeath wealth, and participate in other financial activities. The Tanzimat reforms of the nineteenth century created additional rights for women, particularly in the field of education. Some of the first schools for girls were started in 1858, though the curriculum was focused mainly on teaching Muslim wives and mothers.

W

WYedikuleli Seyyid Abdullah Efendi (1670-1731) was an Ottoman master calligrapher.

W

WYesarizade Mustafa Izzet Efendi was an Ottoman calligrapher.

W

WFausto Zonaro was an Italian painter, best known for his Realist style paintings of life and history of the Ottoman Empire.