W

WSenescence or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. The word senescence can refer either to cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence involves an increase in death rates and/or a decrease in fecundity with increasing age, at least in the latter part of an organism's life cycle.

W

WAn aging-associated disease is a disease that is most often seen with increasing frequency with increasing senescence. Essentially, aging-associated diseases are complications arising from senescence. Age-associated diseases are to be distinguished from the aging process itself because all adult animals age, save for a few rare exceptions, but not all adult animals experience all age-associated diseases. Aging-associated diseases do not refer to age-specific diseases, such as the childhood diseases chicken pox and measles. "Aging-associated disease" is used here to mean "diseases of the elderly". Nor should aging-associated diseases be confused with accelerated aging diseases, all of which are genetic disorders.

W

WPleiotropy occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Such a gene that exhibits multiple phenotypic expression is called a pleiotropic gene. Mutation in a pleiotropic gene may have an effect on several traits simultaneously, due to the gene coding for a product used by a myriad of cells or different targets that have the same signaling function.

W

WBiomarkers of aging are biomarkers that could predict functional capacity at some later age better than chronological age. Stated another way, biomarkers of aging would give the true "biological age", which may be different from the chronological age.

W

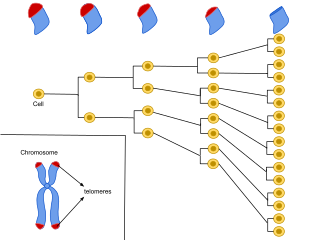

WCellular senescence is a phenomenon characterized by the cessation of cell division. In their groundbreaking experiments during the early 1960s, Leonard Hayflick and Paul Moorhead found that normal human fetal fibroblasts in culture reach a maximum of approximately 50 cell population doublings before becoming senescent. This process is known as "replicative senescence", or the Hayflick limit. Hayflick's discovery of mortal cells paved the path for the discovery and understanding of cellular aging molecular pathways. Cellular senescence can be initiated by a wide variety of stress inducing factors. These stress factors include both environmental and internal damaging events, abnormal cellular growth, oxidative stress, autophagy factors, among many other things.

W

WA centenarian is a person who has reached the age of 100 years. Because life expectancies worldwide are below 100 years, the term is invariably associated with longevity. In 2012, the United Nations estimated that there were 316,600 living centenarians worldwide.

W

WDeath is the permanent, irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. The remains of a previously living organism normally begin to decompose shortly after death. Death is an inevitable, universal process that eventually occurs in all living organisms.

W

WDNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. In human cells, both normal metabolic activities and environmental factors such as radiation can cause DNA damage, resulting in as many as 1 million individual molecular lesions per cell per day. Many of these lesions cause structural damage to the DNA molecule and can alter or eliminate the cell's ability to transcribe the gene that the affected DNA encodes. Other lesions induce potentially harmful mutations in the cell's genome, which affect the survival of its daughter cells after it undergoes mitosis. As a consequence, the DNA repair process is constantly active as it responds to damage in the DNA structure. When normal repair processes fail, and when cellular apoptosis does not occur, irreparable DNA damage may occur, including double-strand breaks and DNA crosslinkages. This can eventually lead to malignant tumors, or cancer as per the two hit hypothesis.

W

WIn molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritance. This is essential for cell division during growth and repair of damaged tissues, while it also ensures that each of the new cells receives its own copy of the DNA. The cell possesses the distinctive property of division, which makes replication of DNA essential.

W

WIn chemistry, a radical is an atom, molecule, or ion that has an unpaired valence electron. With some exceptions, these unpaired electrons make radicals highly chemically reactive. Many radicals spontaneously dimerize. Most organic radicals have short lifetimes.

W

WGenetics of aging is generally concerned with life extension associated with genetic alterations, rather than with accelerated aging diseases leading to reduction in lifespan.

W

WThe Gompertz–Makeham law states that the human death rate is the sum of an age-dependent component, which increases exponentially with age and an age-independent component. In a protected environment where external causes of death are rare, the age-independent mortality component is often negligible. In this case the formula simplifies to a Gompertz law of mortality. In 1825, Benjamin Gompertz proposed an exponential increase in death rates with age.

W

WThe Hayflick limit, or Hayflick phenomenon, is the number of times a normal human cell population will divide before cell division stops.

W

WAn immortalised cell line is a population of cells from a multicellular organism which would normally not proliferate indefinitely but, due to mutation, have evaded normal cellular senescence and instead can keep undergoing division. The cells can therefore be grown for prolonged periods in vitro. The mutations required for immortality can occur naturally or be intentionally induced for experimental purposes. Immortal cell lines are a very important tool for research into the biochemistry and cell biology of multicellular organisms. Immortalised cell lines have also found uses in biotechnology.

W

WInterleukin 8 receptor, beta is a chemokine receptor. IL8RB is also known as CXCR2, and CXCR2 is now the IUPHAR Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug classification-recommended name.

W

WIn gerontology, late-life mortality deceleration is the disputed theory that hazard rate increases at a decreasing rate in late life rather than increasing exponentially as in the Gompertz law.

W

WLife expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, its current age, and other demographic factors including gender. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth (LEB), which can be defined in two ways. Cohort LEB is the mean length of life of an actual birth cohort and can be computed only for cohorts born many decades ago so that all their members have died. Period LEB is the mean length of life of a hypothetical cohort assumed to be exposed, from birth through death, to the mortality rates observed at a given year.

W

WLipofuscin is the name given to fine yellow-brown pigment granules composed of lipid-containing residues of lysosomal digestion. It is considered to be one of the aging or "wear-and-tear" pigments, found in the liver, kidney, heart muscle, retina, adrenals, nerve cells, and ganglion cells. It is specifically arranged around the nucleus, and is a type of lipochrome.

W

WThe word "longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term longevity is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas life expectancy is always defined statistically as the average number of years remaining at a given age. For example, a population's life expectancy at birth is the same as the average age at death for all people born in the same year. Longevity is best thought of as a term for general audiences meaning 'typical length of life' and specific statistical definitions should be clarified when necessary.

W

WMacular degeneration, also known as age-related macular degeneration, is a medical condition which may result in blurred or no vision in the center of the visual field. Early on there are often no symptoms. Over time, however, some people experience a gradual worsening of vision that may affect one or both eyes. While it does not result in complete blindness, loss of central vision can make it hard to recognize faces, drive, read, or perform other activities of daily life. Visual hallucinations may also occur but these do not represent a mental illness.

W

WAge-related memory loss, sometimes described as "normal aging", is qualitatively different from memory loss associated with types of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, and is believed to have a different brain mechanism.

W

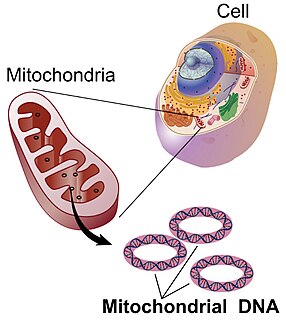

WMitochondrial DNA is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is only a small portion of the DNA in a eukaryotic cell; most of the DNA can be found in the cell nucleus and, in plants and algae, also in plastids such as chloroplasts.

W

WHormesis is a characteristic of many biological processes, namely a biphasic response to exposure to increasing amounts of a substance or condition. Within the hormetic zone, there is generally a favorable biological response to low exposures to toxins and other stressors. The term hormesis comes from Greek hórmēsis "rapid motion, eagerness", itself from ancient Greek hormáein "to set in motion, impel, urge on". The term hormetics has been proposed for the study and science of hormesis.

W

WThe mutation accumulation theory of ageing was first proposed by Peter Medawar in 1952 as an evolutionary explanation for biological ageing and the associated decline in fitness that accompanies it. Medawar used the term 'senescence' to refer to this process. The theory explains that, in the case where harmful mutations are only expressed later in life, when reproduction has ceased and future survival is increasingly unlikely, then these mutations are likely to be unknowingly passed on to future generations. In this situation the force of natural selection will be weak, and so insufficient to consistently eliminate these mutations. Medawar posited that over time these mutations would accumulate due to genetic drift and lead to the evolution of what is now referred to as ageing.

W

WNegligible senescence is a term coined by biogerontologist Caleb Finch to denote organisms that do not exhibit evidence of biological aging (senescence), such as measurable reductions in their reproductive capability, measurable functional decline, or rising death rates with age. There are many species where scientists have seen no increase in mortality after maturity. This may mean that the lifespan of the organism is so long that researchers' subjects have not yet lived up to the time when a measure of the species' longevity can be made. Turtles, for example, were once thought to lack senescence, but more extensive observations have found evidence of decreasing fitness with age.

W

WNeurodegeneration is the progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, including their death. Many neurodegenerative diseases – including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and prion diseases – occur as a result of neurodegenerative processes. Such diseases are incurable, resulting in progressive degeneration of neurons. As research progresses, many similarities appear that relate these diseases to one another on a sub-cellular level. Discovering these similarities offers hope for therapeutic advances that could ameliorate many diseases simultaneously. There are many parallels between different neurodegenerative disorders including atypical protein assemblies as well as induced cell death. Neurodegeneration can be found in many different levels of neuronal circuitry ranging from molecular to systemic.

W

WOxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal redox state of cells can cause toxic effects through the production of peroxides and free radicals that damage all components of the cell, including proteins, lipids, and DNA. Oxidative stress from oxidative metabolism causes base damage, as well as strand breaks in DNA. Base damage is mostly indirect and caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated, e.g. O2− (superoxide radical), OH (hydroxyl radical) and H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide). Further, some reactive oxidative species act as cellular messengers in redox signaling. Thus, oxidative stress can cause disruptions in normal mechanisms of cellular signaling.

W

WPoly(ADP-ribose) polymerase family member 14 is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the PARP14 gene.

W

WPotato root nematodes or potato cyst nematodes (PCN) are 1-mm long roundworms belonging to the genus Globodera, which comprises around 12 species. They live on the roots of plants of the family Solanaceae, such as potatoes and tomatoes. PCN cause growth retardation and, at very high population densities, damage to the roots and early senescence of plants. The nematode is not indigenous to Europe but originates from the Andes. Fields are free from PCN until an introduction occurs, after which the typical patches, or hotspots, occur on the farmland. These patches can become full field infestations when unchecked. Yield reductions can average up to 60% at high population densities.

W

WProgeria is a specific type of progeroid syndrome called Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome. Progeroid syndromes are a group of diseases with premature aging. Patients born with progeria typically live to an age of mid-teens to early twenties.

W

WPyrimidine dimers are molecular lesions formed from thymine or cytosine bases in DNA via photochemical reactions. Ultraviolet light (UV) induces the formation of covalent linkages between consecutive bases along the nucleotide chain in the vicinity of their carbon–carbon double bonds. The dimerization reaction can also occur among pyrimidine bases in dsRNA —uracil or cytosine. Two common UV products are cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6–4 photoproducts. These premutagenic lesions alter the structure and possibly the base-pairing. Up to 50–100 such reactions per second might occur in a skin cell during exposure to sunlight, but are usually corrected within seconds by photolyase reactivation or nucleotide excision repair. Uncorrected lesions can inhibit polymerases, cause misreading during transcription or replication, or lead to arrest of replication. Pyrimidine dimers are the primary cause of melanomas in humans.

W

WIn chemistry, a radical is an atom, molecule, or ion that has an unpaired valence electron. With some exceptions, these unpaired electrons make radicals highly chemically reactive. Many radicals spontaneously dimerize. Most organic radicals have short lifetimes.

W

WReactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemical molecules formed due to the electron acceptability of O2. Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

W

WIn biology, regeneration is the process of renewal, restoration, and tissue growth that makes genomes, cells, organisms, and ecosystems resilient to natural fluctuations or events that cause disturbance or damage. Every species is capable of regeneration, from bacteria to humans. Regeneration can either be complete where the new tissue is the same as the lost tissue, or incomplete where after the necrotic tissue comes fibrosis.

W

WThe selection shadow is a concept involved with the evolutionary theories of aging that states that selection pressures on an individual decrease as an individual ages and passes sexual maturity, resulting in a "shadow" of time where selective fitness is not considered. Over generations, this results in maladaptive mutations that accumulate later in life due to aging being non-adaptive toward reproductive fitness. The concept was first worked out by J. B. S. Haldane and Peter Medawar in the 1940s, with Medawar creating the first graphical model.

W

WSerotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vasoconstriction.

W

WStarfish, or sea stars, are radially symmetrical, star-shaped organisms of the phylum Echinodermata and the class Asteroidea. Aside from their distinguished shape, starfish are most recognized for their remarkable ability to regenerate, or regrow, arms and, in some cases, entire bodies. While most species require some part of the central body to be intact in order to regenerate arms, a few tropical species can grow an entirely new starfish from a portion of a severed limb. Starfish regeneration across species follows a common three-phase model and can take up to a year or longer to complete. Though regeneration is used to recover limbs eaten or removed by predators, starfish are also capable of autotomizing and regenerating limbs to evade predators and reproduce.

W

WA supercentenarian is someone who has reached the age of 110. This age is achieved by about one in 1,000 centenarians. Anderson et al. concluded that supercentenarians live a life typically free of major age-related diseases until shortly before maximum human lifespan is reached.

W

WSuspended animation is the temporary slowing or stopping of biological function so that physiological capabilities are preserved. It may be either hypometabolic or ametabolic in nature. It may be induced by either endogenous, natural or artificial biological, chemical or physical means. In its natural form it may be spontaneously reversible as in the case of species demonstrating hypometabolic states of hibernation or require technologically mediated revival when applied with therapeutic intent in the medical setting as in the case of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA).

W

WTelomerase, also called terminal transferase, is a ribonucleoprotein that adds a species-dependent telomere repeat sequence to the 3' end of telomeres. A telomere is a region of repetitive sequences at each end of the chromosomes of most eukaryotes. Telomeres protect the end of the chromosome from DNA damage or from fusion with neighbouring chromosomes. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster lacks telomerase, but instead uses retrotransposons to maintain telomeres.

W

WYippee-like 3 (Drosophila) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the YPEL3 gene. YPEL3 has growth inhibitory effects in normal and tumor cell lines. One of five family members (YPEL1-5), YPEL3 was named in reference to its Drosophila melanogaster orthologue. Initially discovered in a gene expression profiling assay of p53 activated MCF7 cells, induction of YPEL3 has been shown to trigger permanent growth arrest or cellular senescence in certain human normal and tumor cell types. DNA methylation of a CpG island near the YPEL3 promoter as well as histone acetylation may represent possible epigenetic mechanisms leading to decreased gene expression in human tumors.