W

WVenetian Dalmatia refers to parts of Dalmatia under the rule of the Republic of Venice, mainly from the 16th to the 18th centuries. The first possessions were acquired around 1000, having taken the coastal parts of the Kingdom of Croatia, but Venetian Dalmatia was fully consolidated from 1420 and lasted until 1797 when the republic disappeared with Napoleon's conquests.

W

WThe Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic, traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and maritime republic in parts of present-day Italy which existed from 697 AD until 1797 AD. Centered on the lagoon communities of the prosperous city of Venice, it incorporated numerous overseas possessions in modern Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Greece, Albania and Cyprus. The republic grew into a trading power during the Middle Ages and strengthened this position in the Renaissance. Citizens spoke the still-surviving Venetian language, although publishing in (Florentine) Italian became the norm during the Renaissance.

W

WAndrea Alessi was a Venetian Dalmatian architect and sculptor born in Durazzo, considered one of the most distinguished artists of Dalmatia.

W

WThomas the Archdeacon, also known as Thomas of Split, was a Roman Catholic cleric, historian and chronicler from Split. He is often referred to as one of the greatest sources in the historiography of Croatian lands.

W

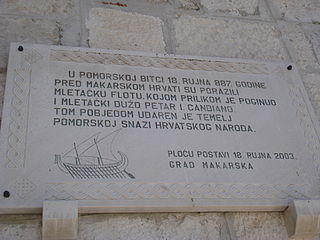

WThe Croatian–Venetian wars were a series of periodical, punctuated medieval conflicts and naval campaigns waged for control of the northeastern coast of the Adriatic Sea between the City-state of Venice and the Principality of Croatia, at times allied with neighbouring territories – the Principality of the Narentines and Zahumlje in the south and Istrian peninsula in the north. First struggles occurred at the very beginning of the existence of two conflict parties, they intensified in the 9th century, lessened during the 10th century, but intensified again since the beginning of the 11th century.

W

WAlberto Fortis (1741–1803) was a Venetian writer, naturalist and cartographer.

W

WStojan Janković Mitrović was the commander of the Morlach troops in the service of the Republic of Venice, from 1669 until his death in 1687. He participated in the Cretan and Great Turkish War, as the supreme commander of the Venetian Morlach troops, of which he is enumerated in Croatian and Serbian epic poetry. He was one of the best-known uskok/hajduk leaders of Dalmatia.

W

WThe Siege of Lastovo in 1000 was part of the campaign of Doge Pietro II Orseolo in southern Croatia and its bloodiest armed conflict between the citizens of Lastovo island and the army of the Venice. The siege resulted in a Venetian victory and Lastovo became part of the Venetian Republic for a while.

W

WJohannes Lucius was a Dalmatian historian, whose greatest work is De regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae, which includes valuable historical sources, a bibliography and six historical maps.

W

WVuk Mandušić was the capo direttore of the Morlach army, one of the most prominent harambaša in the Dalmatian hinterland, that fought the Ottoman Empire during the Cretan War (1645–69). He is one of the heroes renowned in both Croatian, and Serbian epic poetry. The Serb poet-prince-bishop Petar II Petrović Njegoš immortalized him in one of his epic poems, Gorski vjenac, also known in English translation as Mountain Wreath.

W

WGiovanni Thomas Marnavich or Joannes Thomas Marnavich or Ivan Tomko Mrnavić was a Roman Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Bosnia (1631–1639) and an author of historical works. He was the author of several forgeries, with the most famous being that of the Life of Justinian. He also wrote a book on the Life of Saint Sava.

W

WMarko Marulić Splićanin, in Latin Marcus Marulus Spalatensis and Italian Marco Marulo, was a Croatian poet and Renaissance humanist. He coined the term "psychology".

W

WMorlachs has been an exonym used for a rural Christian community in Herzegovina, Lika and the Dalmatian Hinterland. The term was initially used for a Vlach pastoralist community in the mountains of Croatia in the second half of the 14th until the early 16th century. Later, when the community straddled the Venetian–Ottoman border in the 17th century, it referred to Slavic-speaking, mainly Eastern Orthodox but also Roman Catholic people. The Vlach ie Morlach population of Herzegovina and Dalmatian hinterland from the Venetian and Turkish side were of either Roman Catholic or Christian Orthodox faith. Venetian sources from 17th and 18th century make no distinction between Orthodox and Catholics, they call all Christians as Morlacs. The exonym ceased to be used in an ethnic sense by the end of the 18th century, and came to be viewed as derogatory, but has been renewed as a social or cultural anthropological subject. With the nation-building in the 19th century, the population of the Dalmatian Hinterland espoused either a Serb or Croat ethnic identity, but preserved some common sociocultural outlines.

W

WBajo Pivljanin was a hajduk commander mostly active in the Ottoman territories of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia. Born in Piva, at the time part of the Ottoman Empire, he was an oxen trader who allegedly left his village after experiencing Ottoman injustice. Mentioned in 1654 as a brigand during the Venetian–Ottoman war, he entered the service of the Republic of Venice in 1656. The hajduks were used to protect Venetian Dalmatia. He remained a low-rank hajduk for the following decade, participating in some notable operations such as the raid on Trebinje. Between 1665 and 1668 he quickly rose through the ranks to the level of harambaša. After the war, which ended unfavourably for the Venetians, the hajduks were moved out of their haven in the Bay of Kotor under Ottoman pressure. Between 1671 and 1684 Pivljanin, along with other hajduks and their families, were refugees in Dalmatia. Upon renewed conflict, he was returned to the Bay of Kotor and placed in charge of defending the frontier; in 1685 he and his band fell in battle against the advancing Ottoman governor of Scutari. Regarded as one of the most distinguished hajduks of his time, he is praised in Serbian epic poetry.

W

WIvan Krstitelj Rabljanin (1470–1540) was a famous cannon and bell founder in bronze; born in Rab, most of his works are in Dubrovnik.

W

WRavni Kotari is a geographical region in Croatia. It lies in northern Dalmatia, around Zadar and east of it. It is bordered by Bukovica to the northeast, lower Krka to the southeast, and the Adriatic Sea. The largest settlement in the region is the town of Benkovac. Other large settlements are Zemunik Donji, Polača, Poličnik, Galovac, Gorica, Škabrnja, Posedarje, Pridraga, Novigrad, and Stankovci.

W

WThe Siege of Zara or Siege of Zadar was the first major action of the Fourth Crusade and the first attack against a Catholic city by Catholic crusaders. The crusaders had an agreement with Venice for transport across the sea, but the price far exceeded what they were able to pay. Venice set the condition that the crusaders help them capture Zadar, a constant battleground between Venice on one side and Croatia and Hungary on the other, whose king, Emeric, pledged himself to join the Crusade. Although some of the crusaders refused to take part in the siege, the attack on Zadar began in November 1202 despite letters from Pope Innocent III forbidding such an action and threatening excommunication. Zadar fell on 24 November and the Venetians and the crusaders sacked the city. After spending the winter in Zadar the Fourth Crusade continued its campaign, which led to the Siege of Constantinople.

W

WThe Siege of Zadar was a successful attempt of the Republic of Venice to capture Zadar, a Croatian coastal city in northern Dalmatia. It was a combined land and sea offensive by the Venetians, consisting of many separate battles and operations against the citizens of Zadar, who refused to accept Venetian suzerainty and demanded autonomy. Despite receiving military aid from Croato-Hungarian king Louis the Angevin, Zadar was unable to resist the siege and was finally defeated.