W

WThe danka system , also known as jidan system is a system of voluntary and long-term affiliation between Buddhist temples and households in use in Japan since the Heian period. In it, households financially support a Buddhist temple which, in exchange, provides for their spiritual needs. Although its existence long predates the Edo period (1603–1868), the system is best known for its repressive use made at that time by the Tokugawa, who made the affiliation with a Buddhist temple compulsory to all citizens.

W

WFuke-shū or Fuke Zen was a distinct and ephemeral derivative school of Japanese Zen Buddhism which originated as an offshoot of the Rinzai school during the nation's feudal era, lasting from the 13th century until the late 19th century. The sect, or sub-sect, traced its philosophical roots to the eccentric Zen master Puhua, as well as similarities and correspondences with the early Linji House and previous Chán traditions—particularly Huineng's "Sudden Enlightenment" —in Tang Dynasty China.

W

WThe komusō were a group of Japanese mendicant monks of the Fuke school of Zen Buddhism who flourished during the Edo period of 1600–1868. Komusō were characterized by a straw bascinet worn on the head, manifesting the absence of specific ego. They were also known for playing solo pieces on the shakuhachi. These pieces, called honkyoku, were played during a meditative practice called suizen, for alms, as a method of attaining enlightenment, and as a healing modality. The Japanese government introduced reforms after the Edo period, abolishing the Fuke sect. Records of the musical repertoire survived, and are being revived in the 21st century.

W

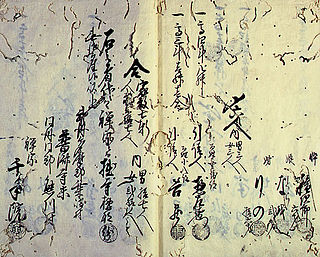

WSenjafuda are votive slips or placards posted on the gates or buildings of shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan. The stickers bear the name of the worshipper, and can be purchased pre-printed with common names at temples and shrines throughout Japan, as well as at stationery stores and video game centres. Senjafuda were originally made from wooden slats, but have been made of paper since the Edo period.

W

WThe Japanese term shinbutsu bunri (神仏分離) indicates the separation of Shinto from Buddhism, introduced after the Meiji Restoration which separated Shinto kami from buddhas, and also Buddhist temples from Shinto shrines, which were originally amalgamated. It is a yojijukugo phrase.

W

WShinbutsu-shūgō, also called Shinbutsu-konkō, is the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism that was Japan's only organized religion up until the Meiji period. Beginning in 1868, the new Meiji government approved a series of laws that separated Japanese native kami worship, on one side, from Buddhism which had assimilated it, on the other.

W

WThe Thirteen Buddhas is a Japanese grouping of Buddhist deities, particularly in the Shingon sect of Buddhism. The deities are, in fact, not only Buddhas, but include bodhisattvas and Wisdom Kings. In Shingon services, lay followers recite a devotional mantra to each figure, though in Shingon practice, disciples will typically devote themselves to only one, depending on what the teacher assigns. Thus the chanting of the mantras of the Thirteen Buddhas are merely the basic practice of laypeople.

W

WVajrayāna along with "Mantrayāna", "Ghuyamantra", "Tantrayāna", "Tantric Buddhism" and "Esoteric Buddhism" are names referring to Buddhist traditions associated with Tantra and "Secret Mantra", which were taught in private by Buddha Shakyamuni and later practiced in medieval India. Vajrayana was fully revealed in Tibet by Guru Padmasambhava around 767. Vajrayana then spread to East Asia, Mongolia and other Himalayan states, and later to Europe, Russia, and the Americas.