W

WMutualism describes the ecological interaction between two or more species where each species has a net benefit. Mutualism is a common type of ecological interaction. Prominent examples include most vascular plants engaged in mutualistic interactions with mycorrhizae, flowering plants being pollinated by animals, vascular plants being dispersed by animals, and corals with zooxanthellae, among many others. Mutualism can be contrasted with interspecific competition, in which each species experiences reduced fitness, and exploitation, or parasitism, in which one species benefits at the "expense" of the other.

W

WAnt–fungus mutualism is a symbiosis seen in certain ant and fungal species, in which ants actively cultivate fungus much like humans farm crops as a food source. In some species, the ants and fungi are dependent on each other for survival. The leafcutter ant is a well-known example of this symbiosis. A mutualism with fungi is also noted in some species of termites in Africa.

W

WCleaning symbiosis is a mutually beneficial association between individuals of two species, where one removes and eats parasites and other materials from the surface of the other. Cleaning symbiosis is well-known among marine fish, where some small species of cleaner fish, notably wrasses but also species in other genera, are specialised to feed almost exclusively by cleaning larger fish and other marine animals. Other cleaning symbioses exist between birds and mammals, and in other groups.

W

WA domatium is a tiny chamber produced by plants that houses arthropods.

W

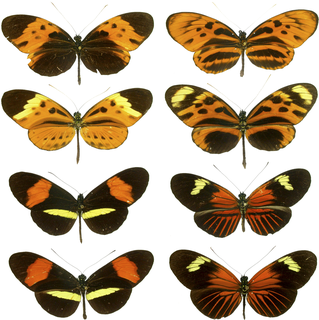

WMüllerian mimicry is a natural phenomenon in which two or more well-defended species, often foul-tasting and that share common predators, have come to mimic each other's honest warning signals, to their mutual benefit. This works because predators can learn to avoid all of them with fewer experiences with members of any one of the relevant species. It is named after the German naturalist Fritz Müller, who first proposed the concept in 1878, supporting his theory with the first mathematical model of frequency-dependent selection, one of the first such models anywhere in biology.

W

WMutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is a 1902 essay collection by Russian naturalist and anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin. The essays, initially published in the English periodical The Nineteenth Century between 1890 and 1896, explore the role of mutually-beneficial cooperation and reciprocity in the animal kingdom and human societies both past and present. It is an argument against theories of social Darwinism that emphasize competition and survival of the fittest, and against the romantic depictions by writers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who thought that cooperation was motivated by universal love. Instead Kropotkin argues that mutual aid has pragmatic advantages for the survival of human and animal communities and, along with the conscience, has been promoted through natural selection.

W

WMyrmecochory is seed dispersal by ants, an ecologically significant ant-plant interaction with worldwide distribution. Most myrmecochorous plants produce seeds with elaiosomes, a term encompassing various external appendages or "food bodies" rich in lipids, amino acids, or other nutrients that are attractive to ants. The seed with its attached elaiosome is collectively known as a diaspore. Seed dispersal by ants is typically accomplished when foraging workers carry diaspores back to the ant colony, after which the elaiosome is removed or fed directly to ant larvae. Once the elaiosome is consumed, the seed is usually discarded in underground middens or ejected from the nest. Although diaspores are seldom distributed far from the parent plant, myrmecochores also benefit from this predominantly mutualistic interaction through dispersal to favourable locations for germination, as well as escape from seed predation.

W

WMyrmecophily is the term applied to positive interspecies associations between ants and a variety of other organisms, such as plants, other arthropods, and fungi. Myrmecophily refers to mutualistic associations with ants, though in its more general use, the term may also refer to commensal or even parasitic interactions.

W

WMany species of Staphylinidae have developed complex interspecies relationships with ants, known as myrmecophily. Rove Beetles are among the most rich and diverse families of myrmecophilous beetles, with a wide variety of relationships with ants. Ant associations range from near free-living species which prey only on ants, to obligate inquilines of ants, which exhibit extreme morphological and chemical adaptations to the harsh environments of ant nests. Some species are fully integrated into the host colony, and are cleaned and fed by ants. Many of these, including species in tribe Clavigerini, are myrmecophagous, placating their hosts with glandular secretions while eating the brood

W

WMyrmecophytes are plants that live in a mutualistic association with a colony of ants. There are over 100 different genera of myrmecophytes. These plants possess structural adaptations that provide ants with food and/or shelter. These specialized structures include domatia, food bodies, and extrafloral nectaries. In exchange for food and shelter, ants aid the myrmecophyte in pollination, seed dispersal, gathering of essential nutrients, and/or defense. Specifically, domatia adapted to ants may be called myrmecodomatia.

W

WA pollination network is a bipartite mutualistic network in which plants and pollinators are the nodes, and the pollination interactions form the links between these nodes. The pollination network is bipartite as interactions only exist between two distinct, non-overlapping sets of species, but not within the set: a pollinator can never be pollinated, unlike in a predator-prey network where a predator can be depredated. A pollination network is two-modal, i.e., it includes only links connecting plant and animal communities.