W

WThis is a select bibliography of post World War II English language books and journal articles about Stalinism and the Stalinist era of Soviet history. Book entries have references to journal reviews about them when helpful and available.

W

WBlack Ribbon Day, officially known in the European Union as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, is an international day of remembrance for victims of totalitarian regimes, specifically Stalinist, communist, Nazi and fascist regimes. Formally recognised by the European Union, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and a number of other countries, it is observed on 23 August and symbolizes the rejection of "extremism, intolerance and oppression". The purpose of the Day of Remembrance is to preserve the memory of the victims of mass deportations and exterminations, while promoting democratic values with the aim to reinforce peace and stability in Europe. It is one of the two official remembrance days or observances of the European Union, alongside Europe Day. Under the name Black Ribbon Day it is also an official remembrance day of Canada, the United States and other countries. The European Union has used both names alongside each other.

W

WBolshevization was the process starting in the mid-1920s by which the pluralistic Comintern and its constituent communist parties were increasingly subject to pressure by the Kremlin in Moscow to follow Marxism–Leninism. The Comintern became a tool of soviet foreign policy. That policy downplayed autonomy in favor of support for the Soviet Union and its foreign policy.

W

WNicolae Ceaușescu was a Romanian communist politician and leader. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He was also the country's head of state from 1967, serving as President of the State Council and from 1974 concurrently as President of the Republic, until his overthrow and execution in the Romanian Revolution in December 1989, part of a series of anti-Communist and anti-Soviet uprisings in Eastern Europe that year.

W

WThe Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International (1919–1943), was an international organization that advocated world communism. It was controlled by the Soviet Union. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state". The Comintern was preceded by the 1916 dissolution of the Second International.

W

WEveryday Stalinism or Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s is a book by Soviet scholar and historian Sheila Fitzpatrick first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press and in paperback in 2000. Sheila Fitzpatrick is the Bernadotte E. Schmitt Distinguished Service Professor (Emeritus), Department of History, University of Chicago.

W

WThe Great Purge or the Great Terror, also known as the Year of '37 and the Yezhovschina, was a campaign of political repression in the Soviet Union that occurred from 1936 to 1938. It involved a large-scale repression of relatively wealthy peasants (kulaks); ethnic cleansing operations against ethnic minorities; a purge of the Communist Party, of government officials, and of the Red Army leadership; widespread police surveillance; suspicion of saboteurs; counter-revolutionaries; imprisonment; and arbitrary executions. Historians estimate the total number of deaths due to Stalinist repression in 1937–38 to be between 950,000 to 1.2 million.

W

WHotel Lux (Люксъ) was a hotel in Moscow that, during the early years of the Soviet Union, housed many leading exiled Communists. During the Nazi era, exiles from all over Europe went there, particularly from Germany. A number of them became leading figures in German politics in the postwar era. Initial reports of the hotel were very good, although its problem with rats was mentioned as early as 1921. Communists from more than 50 countries came for congresses and for training or to work. By the 1930s, Joseph Stalin had come to regard the international character of the hotel with suspicion and its occupants as potential spies. His purges created an atmosphere of fear among the occupants, who were faced with mistrust, denunciations, and nightly arrests. The purges at the hotel peaked between 1936 and 1938. Germans who fled Hitler for safety in the Soviet Union found themselves interrogated, arrested, tortured, and sent to forced labor camps. Most of the 178 leading German communists who were killed in Stalin's purges were residents of Hotel Lux.

W

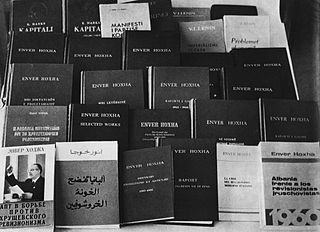

WEnver Hoxha was an Albanian politician who served as the First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania, from 1941 until his death in 1985. He was also a member of Politburo of the Party of Labour of Albania, chairman of the Democratic Front of Albania, commander-in-chief of the armed forces from 1944 until his death. He served as the 22nd Prime Minister of Albania from 1944 to 1954 and at various times served as foreign minister and defence minister of People's Socialist Republic of Albania as well.

W

WHoxhaism is a variant of anti-revisionist Marxism–Leninism that developed in the late 1970s due to a split in the Maoist movement, appearing after the ideological dispute between the Communist Party of China and the Party of Labour of Albania in 1978. The ideology is named after Enver Hoxha, a notable Albanian communist leader, who served as the First Secretary of the Party of Labour.

W

WKim Il-sung was the founder of North Korea, which he ruled from the country's establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. He held the posts of Premier from 1948 to 1972 and President from 1972 to 1994. He was also the leader of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) from 1949 to 1994. Coming to power after the end of Japanese rule in 1945, he authorized the invasion of South Korea in 1950, triggering an intervention in defense of South Korea by the United Nations led by the United States. Following the military stalemate in the Korean War, a ceasefire was signed on 27 July 1953. He was the third longest-serving non-royal head of state/government in the 20th century, in office for more than 45 years.

W

WA number of authors have carried out comparisons of Nazism and Stalinism in which they have considered the similarities and differences of the two ideologies and political systems, what relationship existed between the two regimes, and why both of them came to prominence at the same time. During the 20th century, the comparison of Nazism and Stalinism was made on the topics of totalitarianism, ideology, and personality cult. Both regimes were seen in contrast to the liberal West, with an emphasis on the similarities between the two.

W

WSerpantinka is the informal name for the place of detention and execution at the times of Stalinism, located in the Kolyma region. It was under control of Sevvostlag, and the local NKVD troika used it as the second major place for the enforcement of their death sentences during the Great Terror. The few survivors recall "Serpantinka" as one of the most brutal sites, even among Stalin's camps in the Kolyma area.

W

WThe Stalin tunic or Stalinka is a type of tunic or jacket associated with Joseph Stalin; from the 1920s until the 1950s and beyond, it was commonly worn as a political uniform by government officials in the Soviet Union.

W

WJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet politician who ruled the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s until his death in 1953. During his years in power, he served as both General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–1952) and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (1941–1953). Despite initially governing the country as part of a collective leadership, he ultimately consolidated power to become the Soviet Union's de facto leader by the 1930s. A communist ideologically committed to the Leninist interpretation of Marxism, Stalin formalised these ideas as Marxism–Leninism while his own policies are known as Stalinism.

W

WStalin: Breaker of Nations is a biography of Joseph Stalin by author and historian Robert Conquest. It was published in 1991 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson and Penguin Books.

W

WStalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928 is the first volume of an extensive three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin by American historian and Princeton Professor of History Stephen Kotkin. Originally published in November 2014 by Penguin Random House: Hardcover (ISBN 978-1594203794) and Kindle and as an audiobook in December 2014 by Recorded Books. The second volume, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941, was published in 2017 by Penguin Random House.

W

WStalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 is the second volume in an extensive three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin by American historian and Princeton Professor of History Stephen Kotkin. Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 was originally published in October 2017 by Penguin Random House, and as an audiobook in December 2017 by Recorded Books, and was reprinted as a paperback by Penguin in November 2018. The first volume, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928, was published in 2014 by Penguin Random House and the third and final volume, Miscalculation and the Mao Eclipse is scheduled to be published after 2020.

W

WJoseph Stalin's cult of personality became a prominent feature of Soviet culture in December 1929, after a lavish celebration of his purported 50th birthday. For the rest of Stalin's rule, the Soviet press presented Stalin as an all-powerful, all-knowing leader, with Stalin's name and image appearing everywhere.

W

WStalin's Peasants or Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization is a groundbreaking book by Soviet scholar and historian Sheila Fitzpatrick first published in 1994 by Oxford University Press. It was released in 1996 in a paperback edition and reissued in 2006 by Oxford University Press. Sheila Fitzpatrick is the Bernadotte E. Schmitt Distinguished Service Professor (Emeritus), Department of History, University of Chicago.

W

WThe Berlin Stalin statue was a bronze portrayal of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. A Komsomol delegation had presented the sculpture to the East Berlin government on the occasion of the Third World Festival of Youth and Students in 1951. The monument was formally dedicated on 3 August 1951 after temporarily placement at a location on a newly designed and impressive boulevard, Stalinallee, being constructed at the time in what was then the Berlin district of Friedrichshain. Stalin monuments were generally removed from public view by the leadership of the Soviet Union and other associated countries, including East Germany, during the period of De-Stalinization. In Berlin the statue and all street signs designating Stalinallee were hastily removed one night in a clandestine operation and the street was renamed Karl-Marx-Allee and Frankfurter Allee. The bronze sculpture was smashed and the pieces were recycled.

W

WTankie is a term which originally referred to members of the Communist Party of Great Britain that followed the Kremlin line, agreeing with the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and later the Prague Spring by Soviet tanks; or more broadly, those who followed a traditional pro-Soviet or Stalinist position. More recently it has seen a less specific use of the term, referring to hardline authoritarian or Marxist–Leninist positions on the left.

W

WThe Zhdanov Doctrine was a Soviet cultural doctrine developed by Central Committee secretary Andrei Zhdanov in 1946. It proposed that the world was divided into two camps: the "imperialistic", headed by the United States; and "democratic", headed by the Soviet Union. The main principle of the Zhdanov doctrine was often summarized by the phrase "The only conflict that is possible in Soviet culture is the conflict between good and best". Zhdanovism soon became a Soviet cultural policy, meaning that Soviet artists, writers and intelligentsia in general had to conform to the party line in their creative works. Under this policy, artists who failed to comply with the government's wishes risked persecution. The policy remained in effect until the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953.