W

WMedieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century to the Renaissance in the 15th century. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning.

W

WThe unity of the intellect is a philosophical theory proposed by the medieval Andalusian philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), which asserted that all humans share the same intellect. Averroes expounded his theory in his long commentary of On the Soul to explain how universal knowledge is possible within the Aristotelian theory of mind. Averroes's theory was influenced by related ideas by previous thinkers such as Aristotle, Plotinus, Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Avempace.

W

WAztec philosophy was a school of philosophy that developed out of Aztec culture. The Aztecs had a well-developed school of philosophy, perhaps the most developed in the Americas and in many ways comparable to Ancient Greek philosophy, even amassing more texts than the ancient Greeks. Aztec cosmology was in some sense dualistic, but exhibited a less common form of it known as dialectical monism. Aztec philosophy also included ethics and aesthetics. It has been asserted that the central question in Aztec philosophy was how people can find stability and balance in an ephemeral world.

W

WBuridan's Bridge is described by Jean Buridan, one of the most famous and influential philosophers of the Late Middle Ages, in his book Sophismata. It is a self-referential paradox that involves a proposition pronounced about an event that might or might not happen in the future.

W

WThe Hermetica are texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories:The "technical" Hermetica: this category contains a broad variety of treatises dealing with astrology, medicine and pharmacology, alchemy, and magic, the oldest of which were written in Greek and may go back as far as the second or third century BCE. Many of the texts belonging in this category were later translated into Arabic and Latin, often being extensively revised and expanded throughout the centuries. Some of them were also originally written in Arabic, though in many cases their status as an original work or translation remains unclear. These Arabic and Latin Hermetic texts were widely copied throughout the Middle Ages. The "religio-philosophical" Hermetica: this category contains a relatively coherent set of religio-philosophical treatises which were mostly written in the second and third centuries CE, though the very earliest one of them, the Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius, may go back to the first century CE. They are chiefly focused on the relationship between human beings, the cosmos, and God. Many of them are also moral exhortations calling for a way of life leading to spiritual rebirth, and eventually to divinization in the form of a heavenly ascent. The treatises in this category were probably all originally written in Greek, even though some of them only survive in Coptic, Armenian, or Latin translations. During the Middle Ages, most of them were only accessible to Byzantine scholars, until a compilation of Greek Hermetic treatises known as the Corpus Hermeticum was translated into Latin by the Renaissance scholars Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447–1500).

W

WIn the Middle Ages, hierocracy or papalism was a current of Latin legal and political thought that argued that the pope held supreme authority over not just spiritual, but also temporal affairs. In its full, late medieval form, hierocratic theory posited that since Christ was lord of the universe and both king and priest, and the pope was his earthly vicar, the pope must also possess both spiritual and temporal authority over everybody in the world. Papalist writers at the turn of the 14th century such as Augustinus Triumphus and Giles of Rome depicted secular government as a product of human sinfulness that originated, by necessity, in tyrannical usurpation, and could be redeemed only by submission to the superior spiritual sovereignty of the pope. At the head of the Catholic Church, responsible to no other jurisdiction except God, the pope, they argued, was the monarch of a universal kingdom whose power extended to Christians and non-Christians alike.

W

WThe Renaissance is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas and achievements of classical antiquity. It occurred after the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages and was associated with great social change. In addition to the standard periodization, proponents of a "long Renaissance" may put its beginning in the 14th century and its end in the 17th century.

W

WRenaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term humanist referred to teachers and students of the humanities, known as the studia humanitatis, which included grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. It was not until the 19th century that this began to be called humanism instead of the original humanities, and later by the retronym Renaissance humanism to distinguish it from later humanist developments. During the Renaissance period most humanists were Christians, so their concern was to "purify and renew Christianity", not to do away with it. Their vision was to return ad fontes to the simplicity of the New Testament, bypassing the complexities of medieval theology. Today, by contrast, the term humanism has come to signify "a worldview which denies the existence or relevance of God, or which is committed to a purely secular outlook".

W

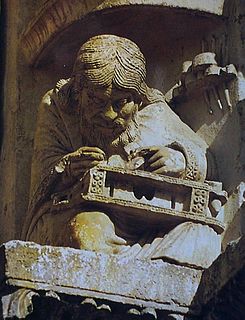

WDuring the High Middle Ages, the Chartres Cathedral established the cathedral School of Chartres, an important center of French scholarship located in Paris. It developed and reached its apex during the transitional period of the 11th and 12th centuries, at the start of the Latin translation movement. This period was also right before the spread of medieval universities, which eventually superseded cathedral schools and monastic schools as the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West.

W

WThe School of Reims was the cathedral school of Reims Cathedral in France that was in operation during the Middle Ages. The term is also used of an artistic style in Carolingian art, lasting into Ottonian art in works such as the gold relief figures on the cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach, which in fact were probably made in Trier in the 890s. Archbishop Ebbo promoted artistic production at the abbey at Hautvillers, near the city. Major works probably made there in the 9th century include: the Ebbo Gospels (816–835), the Utrecht Psalter, which was perhaps the most important of all Carolingian manuscripts, and the Bern Physiologus.

W

WThe school of St Victor was the medieval monastic school at the Augustinian abbey of St Victor in Paris. The name also refers to the Victorines, the group of philosophers and mystics based at this school as part of the University of Paris.

W

WScotistic realism is the Scotist position on the problem of universals. It is a form of moderate realism.

W

WUnivocity of being is the idea that words describing the properties of God mean the same thing as when they apply to people or things. It is associated with the doctrines of the Scholastic theologian John Duns Scotus.