W

WEichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil is a 1963 book by political thinker Hannah Arendt. Arendt, a Jew who fled Germany during Adolf Hitler's rise to power, reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major organizers of the Holocaust, for The New Yorker. A revised and enlarged edition was published in 1964.

W

WThe phrase "the best of all possible worlds" was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal. The claim that the actual world is the best of all possible worlds is the central argument in Leibniz's theodicy, or his attempt to solve the problem of evil.

W

WThe chicken or the egg causality dilemma is commonly stated as the question, "which came first: the chicken or the egg?" The dilemma stems from the observation that all chickens hatch from eggs and all chicken eggs are laid by chickens. "Chicken-and-egg" is a metaphoric adjective describing situations where it is not clear which of two events should be considered the cause and which should be considered the effect, to express a scenario of infinite regress, or to express the difficulty of sequencing actions where each seems to depend on others being done first. Plutarch posed the question as a philosophical matter in his essay "The Symposiacs", written in the 1st century CE.

W

WThe Latin cogito, ergo sum, usually translated into English as "I think, therefore I am", is a philosophical statement that was made by René Descartes. The phrase originally appeared in French as je pense, donc je suis in his 1637 Discourse on the Method, so as to reach a wider audience than Latin would have allowed. It appeared in Latin in his later Principles of Philosophy. The dictum is also sometimes referred to as the cogito. As Descartes explained it, "we cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt." A fuller version, articulated by Antoine Léonard Thomas, aptly captures Descartes' intent: dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum.

W

WNo Exit is a 1944 existentialist French play by Jean-Paul Sartre. The original title is the French equivalent of the legal term in camera, referring to a private discussion behind closed doors. The play was first performed at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in May 1944. The play begins with three characters who find themselves waiting in a mysterious room. It is a depiction of the afterlife in which three deceased characters are punished by being locked into a room together for eternity. It is the source of Sartre's especially famous phrase "L'enfer, c'est les autres" or "Hell is other people", a reference to Sartre's ideas about the look and the perpetual ontological struggle of being caused to see oneself as an object from the view of another consciousness.

W

WHomo homini lupus, or in its unabridged form Homo homini lupus est, is a Latin proverb meaning "A man is a wolf to another man," or more tersely "Man is wolf to man." It has meaning in reference to situations where people are known to have behaved in a way comparably in nature to a wolf. The wolf as a creature is thought, in this example, to have qualities of being predatory, cruel, inhuman i.e. more like an animal than civilized.

W

W"I know that I know nothing" is a saying derived from Plato's account of the Greek philosopher Socrates. It is also called the Socratic paradox. The phrase is not one that Socrates himself is ever recorded as saying.

W

WThe Latin cogito, ergo sum, usually translated into English as "I think, therefore I am", is a philosophical statement that was made by René Descartes. The phrase originally appeared in French as je pense, donc je suis in his 1637 Discourse on the Method, so as to reach a wider audience than Latin would have allowed. It appeared in Latin in his later Principles of Philosophy. The dictum is also sometimes referred to as the cogito. As Descartes explained it, "we cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt." A fuller version, articulated by Antoine Léonard Thomas, aptly captures Descartes' intent: dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum.

W

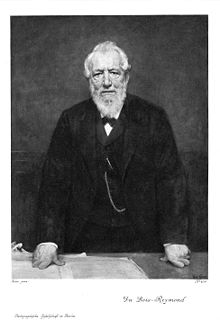

WThe Latin maxim ignoramus et ignorabimus, meaning "we do not know and will not know," represents the idea that scientific knowledge is limited. It was popularized by Emil du Bois-Reymond, a German physiologist, in his 1872 address "Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens"

W

WThe Ancient Greek aphorism "know thyself" is one of the Delphic maxims and was the first of three maxims inscribed in the pronaos (forecourt) of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi according to the Greek writer Pausanias (10.24.1). The two maxims that followed "know thyself" were "nothing to excess" and "certainty brings insanity". In Latin the phrase, "know thyself", is given as nosce te ipsum or temet nosce.

W

W"Language speaks" is a saying by Martin Heidegger. Heidegger first formulated it in his 1950 lecture "Language", and frequently repeated it in later works.

W

W"The medium is the message" is a phrase coined by the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and the name of the first chapter in his Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, published in 1964. McLuhan proposes that a communication medium itself, not the messages it carries, should be the primary focus of study. He showed that artifacts as media affect any society by their characteristics, or content.

W

WNavel-gazing or omphaloskepsis is the contemplation of one's navel as an aid to meditation.

W

WThe opium of the people is a dictum used in reference to religion, derived from the most frequently paraphrased statements of German sociologist and economic theorist Karl Marx: "Religion is the opium of the people." In context, the statement is part of Marx's structural-functionalist argument that religion was constructed by people to calm uncertainty over their role in the universe and in society.

W

WThe Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters or The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters is an aquatint by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya. Created between 1797 and 1799 for the Diario de Madrid, it is the 43rd of the 80 aquatints making up the satirical Los Caprichos.

W

W"The unexamined life is not worth living" is a famous dictum apparently uttered by Socrates at his trial for impiety and corrupting youth, for which he was subsequently sentenced to death, as described in Plato's Apology (38a5–6).

W

WThe political slogan "Workers of the world, unite!" is one of the rallying cries from The Communist Manifesto (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A variation of this phrase is also inscribed on Marx's tombstone. The essence of the slogan is that members of the working classes throughout the world should cooperate to defeat capitalism and achieve victory in the class conflict.