W

WThe Achaemenid Persian Lion Rhyton is an ancient artifact related to Achaemenians.

W

WThe Acropole Tomb was excavated on 6 February 1901 by Jacques de Morgan on the so called acropolis in Susa. The Achaemenide burial was found intact and contained a high number of personal adornments, many of then made in gold. The burial dates around 350 to 332 BC. Most of the objects are now on display in the Louvre in Paris. It is one of the most important Achaemenide treasures ever found.

W

WThe Altıkulaç Sarcophagus, or Çan sarcophagus, is an early 4th century BCE sarcophagus. It is sometimes said to be in the Greco-Persian style. The sarcophagus was found in 1998 in a circular corbel-vaulted tomb within the Çingenetepe tumulus, in the village of Altıkulaç, near Çan, in the eastern Troad, about halfway between Troy and Daskyleion, in what was anciently Hellespontine Phrygia. It was looted and damaged in the process, but a large part of the reliefs remained intact. It is made of painted marble carved in low relief, and dated to the 1st quarter 4th century BCE. It was made at about the same time as the famous tombs in Lycia.

W

WThe Apadana hoard is a hoard of coins that were discovered under the stone boxes containing the foundation tablets of the Apadana Palace in Persepolis. The coins were discovered in excavations in 1933 by Erich Schmidt, in two deposits, each deposit under the two deposition boxes that were found. The deposition of this hoard, which was visibly part of the foundation ritual of the Apadana, is dated to circa 515 BCE.

W

WBardak Siah Palace is the name of the site of an ancient Achaemenid Persian palace situated in the ancient city of Temukan near the township of Borazjan in the northern part of Bushehr Province of Iran. The site was unearthed in 1977 by Iranian archeologists headed by Ehsan Yaghmai

W

WThe Caylus vase is a jar in alabaster dedicated in the name of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I in Egyptian hieroglyph and Old Persian cuneiform. It was the key element in confirming the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform by Grotefend, through the reading of the hieroglyphic part by Champollion in 1823. It also confirmed the antiquity of phonetical hieroglyphs before the time of Alexander the Great, thus corroborating the phonetical decipherment of the names of ancient Egyptian pharaohs. The vase was named after Anne Claude de Tubières, count of Caylus, an early French collector, who had acquired the vase in the 18th century, between 1752 and 1765. It is now located in the Cabinet des Médailles, Paris.

W

WThe Cyrus Cylinder or Cyrus Charter is an ancient clay cylinder, now broken into several pieces, on which is written a declaration in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of Persia's Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great. It dates from the 6th century BC and was discovered in the ruins of Babylon in Mesopotamia in 1879. It is currently in the possession of the British Museum, which sponsored the expedition that discovered the cylinder. It was created and used as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was invaded by Cyrus and incorporated into his Persian Empire.

W

WDarius the Great's Suez Inscriptions were texts written in Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian and Egyptian on five monuments erected in Wadi Tumilat, commemorating the opening of the "Canal of the Pharaohs", between the Nile and the Bitter Lakes.

W

WThe Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of papyri and ostraca in hieratic and demotic Egyptian, Aramaic, Koine Greek, Latin and Coptic, spanning a period of 100 years. The documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives, and are thus an invaluable source of knowledge for scholars of varied disciplines such as epistolography, law, society, religion, language and onomastics. They are a collection of ancient Jewish manuscripts dating from the 5th century BCE. They come from a Jewish community at Elephantine, then called ꜣbw. The dry soil of Upper Egypt preserved the documents.

W

WThe Eshmunazar II sarcophagus is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the "Phoenician Necropolis", a hypogeum complex in the southern area of the city of Sidon in modern-day Lebanon. The sarcophagus was discovered by members of the French consulate in Sidon and was donated to the Louvre. The Eshmunazar II sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and the other on its trough, under the sarcophagus head. The lid engraving was of great significance upon its discovery; it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper, the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is the second longest extant Phoenician inscription after the one discovered at Karatepe.

W

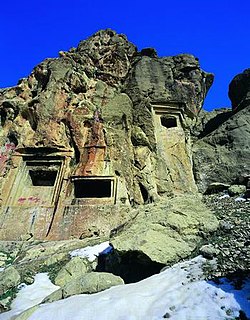

WThe Essaqwand Rock Tombs are three rock-hewn tombs located 25 km southwest of Harsin in Kermanshah Province, Iran. On top of the middle tomb there is a rock relief of a man with his profile toward the viewers. He is holding his hands in prayers in front of him. There is also a torch and a fire altar in front of him. Behind the fire altar there is another man, holding up something in his hands. The tombs have been attributed to different historical eras including Medes, Achaemenids, Seleucids and Parthians.

W

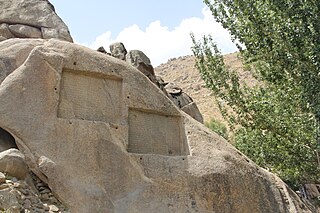

WGanjnameh is located 12 km southwest of Hamadan in western Iran, at an altitude of c. 2000 meters across Mount Alvand. The site is home to two trilingual Achaemenid cuneiform inscriptions. The inscription on the upper left was created on the order of Achaemenid King Darius the Great and the one on the right by his son King Xerxes the Great.

W

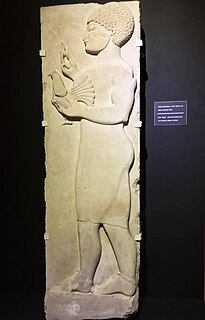

WThe Gökçeler relief is an Achaemenid-era tomb relief made in the Anatolian-Persian style. It was found in 2004 in the village of Gökçeler in Manisa Province of present-day Turkey. The area of discovery corresponds to the northern part of the historic region of Lydia, at a time when it was a satrapy (province) of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The relief is made out of limestone and measures 1.79m × 0.55m × 0.25m. The relief is a "distinctive product of the artistic synthesis classified as Graeco-Persian or Anatolian-Persian". It was created between the late 6th century and early 5th century BC. It may be used as "yet further evidence for the presence of Persians in the region".

W

WThe Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approximately 480–470 BC, the chamber topped a tall pillar and was decorated with marble panels carved in bas-relief. The tomb was built for an Iranian prince or governor of Xanthus, perhaps Kybernis.

W

WThe Harran Stela was discovered in 1956 in the ruins of Harran, in what is now southeast Turkey. It consists of two parts, both of which show, at the top, Nabonidus worshipping symbols of the Sun, Ishtar, and the moon-god Sin. The stela is significant as a genuine text from Nabonidus that demonstrates his adoration of these deities, especially of Sin, which was a departure from the traditional Babylonian exaltation of Marduk as the chief god of the heavenly pantheon. According to Paul-Alain Beaulieu, the Stela was composed in the latter part of his reign, probably the fourteenth or fifteenth year, i.e. 542–540 BC.

W

WThe Herakleia head is the portrait of a probable Achaemenid Satrap of Asia Minor of the late 6th century, found in Heraclea, in Bithynia, modern Turkey. The head is now located in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

W

WThe Jar of Xerxes I is a jar in calcite or alabaster, an alabastron, with the quadrilingual signature of Achaemenid ruler Xerxes I, which was discovered in the ruins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, in Caria, modern Turkey, at the foot of the western staircase. It is now in the British Museum.

W

WLakh Mazar Inscription is a prehistory stone wall located near the Kooch village, about 29 km away from Birjand in Iran. It is the most valuable memorial plaque in east of Iran due to its diversity and historical importance. These inscriptions were discovered by the Birjand Historical Research group and after preliminary studies, 307 images including a collection of inscriptions and motifs on the rocky mountains of Bagheran were identified and at the very beginning they considered their cultural content and features as heritages from the past. In Lakh Mazar Inscription in Birjand, you will see different images that have survived from different periods and have taken a few thousand years of our land. Each of these paintings has their own style according to their period and every single of them can be analyzed on its own. As a general category, Lakh Mazar Inscription in Birjand can be divided into four major groups, stone period, and prehistoric, historical and Islamic periods. Lakh Mazar Inscription in Birjand were observed with signs of human, animal and plant pictorial lines and signs and symbols of manifestations of nature. From these 307 paintings and engravings on these rocks, 22 of them relate to the role of man, 33 relate to the role of the animal, 35 plant's role, 4 pictorial lines, 81 inscriptions of the Pahlavi Parthian and Sassanid and 42 includes Persian and Arabic inscriptions, 67 of these rock paintings have not been identified yet. In order to visit such an amazing inscription you must go to South Khorasan Province.

W

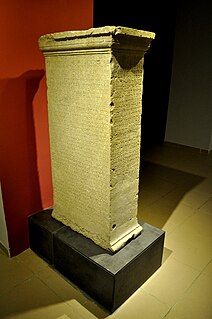

WThe Letoon trilingual, or Xanthos trilingual, is an inscription in three languages: standard Lycian or Lycian A, Greek, and Aramaic covering the faces of a four-sided stone stele called the Letoon Trilingual Stele, discovered in 1973 during the archeological exploration of the Letoon temple complex, near Xanthos, ancient Lycia, in present-day Turkey. It was created when Lycia was under the sway of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. The inscription is a public record of a decree authorizing the establishment of a cult, with references to the deities, and provisions for officers in the new cult. The Lycian requires 41 lines; the Greek, 35 and the Aramaic, 27. They are not word-for-word translations, but each contains some information not present in the others. The Aramaic is somewhat condensed.

W

WThe Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon is a sarcophagus discovered in the Ayaa necropolis, in Sidon, Lebanon. It is made of Parian marble, and resembles the shapes of ogival Lycian tombs, hence its name. It is now located in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. It is dated to circa 430-420 BC. This sarcophagus, as well as others in the Sidon necropolis, belonged to a succession of kings who ruled in the area of Phoenicia between the mid-5th century BC to the end of the 4th century BC.

W

WThe Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC in Halicarnassus for Mausolus, a native Anatolian from Caria and a satrap in the Achaemenid Empire, and his sister-wife Artemisia II of Caria. The structure was designed by the Greek architects Satyros and Pythius of Priene. Its elevated tomb structure is derived from the tombs of neighbouring Lycia, a territory Mausolus had invaded and annexed circa 360 BC, such as the Nereid Monument.

W

WNaqsh-e Rostam is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the face of the mountain and the mountain contains the final resting place of four Achaemenid kings notably king Darius the Great and his son, Xerxes. This site is of great significance to the history of Iran and to Iranians, as it contains various archeological sites carved into the rock wall through time for more than a millennium from the Elamites and Achaemenids to Sassanians. It lies a few hundred meters from Naqsh-e Rajab, with a further four Sassanid rock reliefs, three celebrating kings and one a high priest.

W

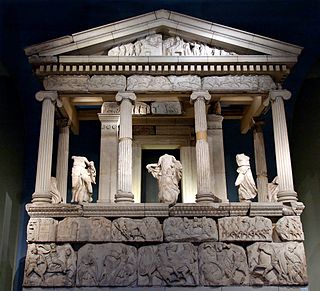

WThe Nereid Monument is a sculptured tomb from Xanthos in Lycia, close to present-day Fethiye in Mugla Province, Turkey. It took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built in the early fourth century BC as a tomb for Arbinas, the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia under the Achaemenid Empire.

W

WThe Oxus treasure is a collection of about 180 surviving pieces of metalwork in gold and silver, most relatively small, and around 200 coins, from the Achaemenid Persian period which were found by the Oxus river about 1877–1880. The exact place and date of the find remain unclear, but is often proposed as being near Kobadiyan. It is likely that many other pieces from the hoard were melted down for bullion; early reports suggest there were originally some 1500 coins, and mention types of metalwork that are not among the surviving pieces. The metalwork is believed to date from the sixth to fourth centuries BC, but the coins show a greater range, with some of those believed to belong to the treasure coming from around 200 BC. The most likely origin for the treasure is that it belonged to a temple, where votive offerings were deposited over a long period. How it came to be deposited is unknown.

W

WPasargadae was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great, who ordered its construction and the location of his tomb. Today it is an archaeological site and one of Iran's UNESCO World Heritage Sites, about 90 kilometres (56 mi) to the northeast of the modern city of Shiraz.

W

WThe Persepolis Fortification Archive and Persepolis Treasury Archive are two groups of clay administrative archives — sets of records physically stored together – found in Persepolis dating to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The discovery was made during legal excavations conducted by the archaeologists from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in the 1930s. Hence they are named for their in situ findspot: Persepolis. The archaeological excavations at Persepolis for the Oriental Institute were initially directed by Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934 and carried on from 1934 until 1939 by Erich Schmidt.

W

WThe Polyxena sarcophagus is a late 6th century BCE sarcophagus from Hellespontine Phrygia, at the beginning of the period when it became a Province of the Achaemenid Empire. The sarcophagus was found in the Kızöldün tumulus, in the Granicus river valley, near Biga in the Province of Çanakkale in 1994. The area where the sarcophagus was found is located midway between Troy and Daskyleion, the capital of Hellespontine Phrygia.

W

WQadamgah or Chasht-Khor is an Achaemenid rock-cut monument at the southeastern part of the Kuh-e Rahmat mountain in Fars Province of Iran, about 40 km south of Persepolis. It consists of three platforms with rear walls and staircases, and features cavities on the back wall and a now-dry spring and pond at the bottom. Its function has been a matter of debate, with latest research pointing to a religious function related to the holy element Water.

W

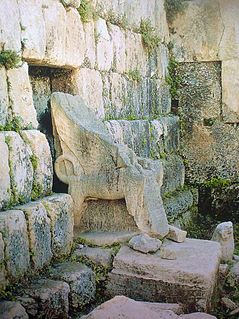

WThe Temple of Eshmun is an ancient place of worship dedicated to Eshmun, the Phoenician god of healing. It is located near the Awali river, 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Sidon in southwestern Lebanon. The site was occupied from the 7th century BC to the 8th century AD, suggesting an integrated relationship with the nearby city of Sidon. Although originally constructed by Sidonian king Eshmunazar II in the Achaemenid era to celebrate the city's recovered wealth and stature, the temple complex was greatly expanded by Bodashtart, Yatan-milk and later monarchs. Because the continued expansion spanned many centuries of alternating independence and foreign hegemony, the sanctuary features a wealth of different architectural and decorative styles and influences.

W

WThe Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia at the time, in around 360 BC. The tomb was discovered in 1838 and brought to England in 1844 by the explorer Sir Charles Fellows. He described it as a 'Gothic-formed Horse Tomb'. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Tomb of Payava, the Harpy Tomb and the Nereid Monument were built according to the main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

W

WXanthos, also called Xanthus, was a chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia. Many of the tombs at Xanthos are pillar tombs, formed of a stone burial chamber on top of a large stone pillar. The body would be placed in the top of the stone structure, elevating it above the landscape. The tombs are for men who ruled in a Lycian dynasty from the mid-6th century to the mid-4th century BCE and help to show the continuity of their power in the region. Not only do the tombs serve as a form of monumentalization to preserve the memory of the rulers, but they also reveal the adoption of Greek style of decoration.

W

WThe Fortress of Van is a massive stone fortification built by the ancient kingdom of Urartu during the 9th to 7th centuries BC, and is the largest example of its kind. It overlooks the ruins of Tushpa, the ancient Urartian capital during the 9th century, which was centered upon the steep-sided bluff where the fortress now sits. A number of similar fortifications were built throughout the Urartian kingdom, usually cut into hillsides and outcrops in places where modern-day Armenia, Turkey and Iran meet. Successive groups such as the Medes, Achaemenids, Armenians, Parthians, Romans, Sassanid Persians, Byzantines, Arabs, Seljuks, Safavids, Afsharids, Ottomans and Russians each controlled the fortress at one time or another. The ancient fortress is located just west of Van and east of Lake Van in the Van Province of Turkey.

W

WThe Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a stele bearing an inscription currently believed to be trilingual, found on the acropolis of the ancient Lycian city of Xanthos, or Xanthus, near the modern town of Kınık in southern Turkey. It was created when Lycia was part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dates in all likelihood to ca. 400 BC. The pillar is seemingly a funerary marker of a dynastic satrap of Achaemenid Lycia. The dynast in question is mentioned of the stele, but his name had been mostly defaced in the several places where he is mentioned: he could be Kherei (Xerei) or more probably his predecessor Kheriga.

W

WThe Xerxes I inscription at Van, also known as the XV inscription, is a trilingual cuneiform inscription of the Achaemenid King Xerxes I. It is located on the southern slope of a mountain adjacent to the Van Fortress, near Lake Van in present-day Turkey. When inscribed it was located in the Achaemenid province of Armenia. The inscription is inscribed on a smoothed section of the rock face near the fortress, approximately 20 metres above the ground. The niche was originally carved out by Xerxes' father, King Darius, but he left the surface blank.

W

WThe Ziwiye hoard is a treasure hoard containing gold, silver, and ivory objects, also including a few gold pieces with the shape of human face, that was uncovered on in Ziwiyeh plat near Saqqez city in Kurdistan Province, Iran, in 1947.

W

WThe Zvenigorodsky seal, sometimes dubbed "Persian king and the defeated enemies", is an Achaemenid cylinder seal made from chalcedony, and housed in the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg, Russia since 1930, when it was acquired from a private collection. It is the so-called "Zvenigorodsky seal", it was acquired in Kertch, and first appears in the 1881 Compte rendu de la Commission Impériale Archéologique pour l'Année 1881.